BFCM 30% OFF ALL LIVE FEEDS

Every live feed is 30% off—Tisbe, Apocyclops, Rotifers, Phyto, and more. Limited-time BFCM deal!

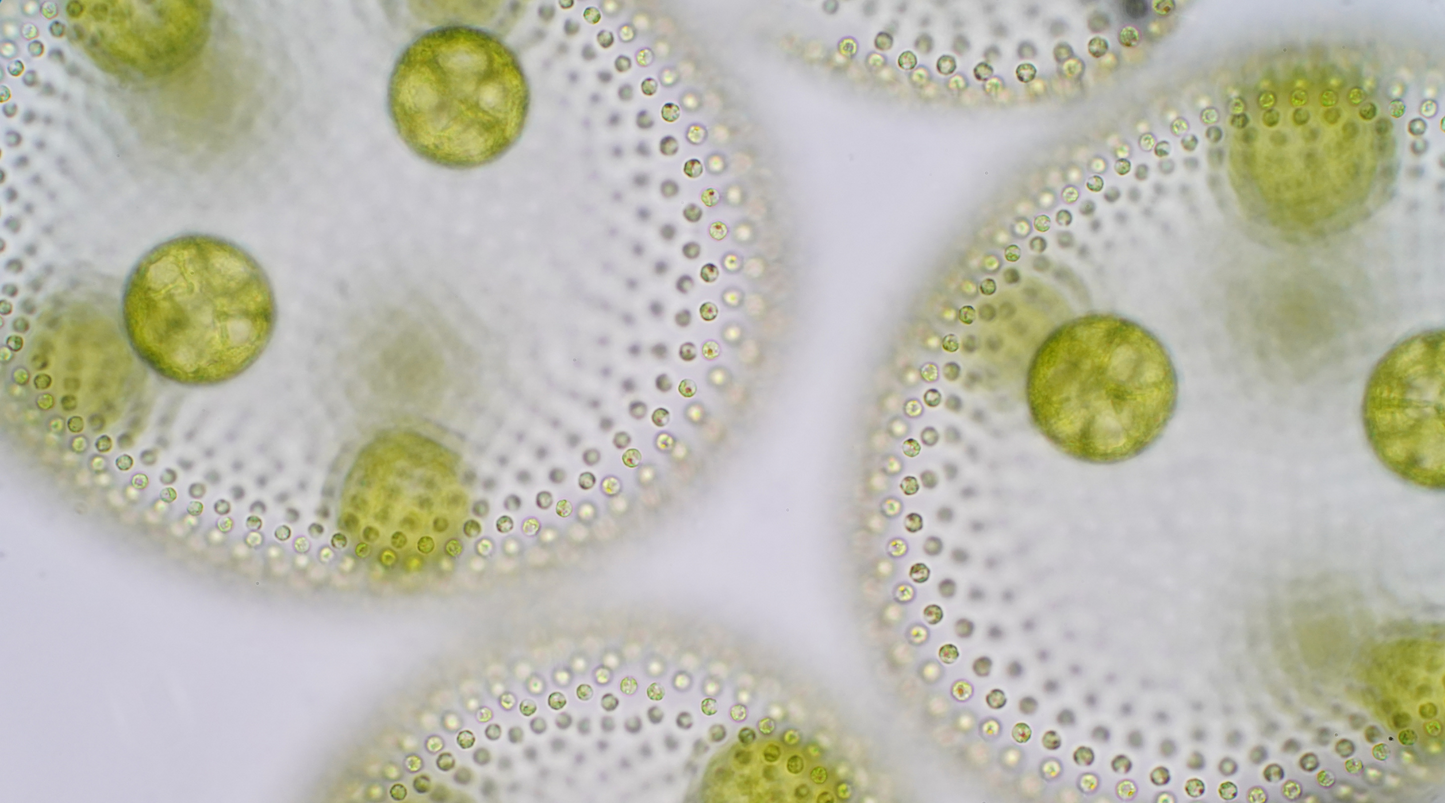

Nannochloropsis sp. is one of the most prolific and powerful tools to the modern reef aquarist, fish breeder, coral farmer and research aquaculturist alike. Nannochloropsis is survivalist algae, one which persists in fresh, salt and brackish water. This extreme elastic ability to adapt can be attributed to the many novel biochemical compounds this algae can produce, many of which offer profound nutritional benefits to the organisms which consume them. Nannochloropsis has been widely utilized in the realm of human nutraceuticals and it has true potential as a sustainable alternative to fish oil. The benefits of this algae go beyond direct consumption, as it has been successfully applied as both a biofiltration agent as well as a live feed in greenwater culture. There is also rising evidence that certain strains of Nannochloropsis exhibit novel antimicrobial and antiviral behaviors. With its many abilities combined with its ease of care, Nannochloropsis has infinite applications in all realms of aquatic husbandry.

Nannochloropsis has evolved an additional power from plants—the ability to construct cell walls making them resistant to foraging from ciliates and other small, contaminating microorganisms. Larger zooplankton, such as rotifers and copepods, are fully capable of annihilating this cell wall and therefore can be grown and gut-loaded on Nannochloropsis diets.

One of the most popular applications of Nannochloropsis is Green Water Aquaculture. With this technique, microalgae is not treated as a direct feed but as the base of a controlled ecosystem. Live Nannochloropsis cells act as the ecosystem base, absorbing ammonia and phosphates, while acting as a food source for rotifers, copepods and other live feeds in the system. These secondary grazers act as constantly available algae-loaded forage for whatever larvae is being reared. The fact that the algae tints the water green helps shade sensitive larvae from over illumination as well. The Green Water Aquaculture technique allowed for the first commercial production of clownfish (Amphiprion sp.), and since then has been applied to the larviculture of anthias, groupers, butterflyfish, damselfish, rabbitfish, seahorses, cobia, porgies, snook, sablefish and countless other marine species.

Many Nannochloropsis species can survive under a wide range of salinities, temperatures and light intensities. These conditions in a reef aquarium (i.e. high illumination, high salinity, low nutrients) exponentially enhance the nutritional profile of Nannochloropsis cells. For example, Abidin et al 2021 demonstrated that Nannochloropsis oculata produced elevated levels of accessory pigments (astaxanthin, canthaxanthin, beta carotene etc.) at salinities greater than 30 ppt. Pal et al 2011 observed that Nannochloropsis oculata produced the most triglycerides and proteins at high light intensities (500-700 PAR[1]). Su et al 2011 demonstrated that Nannochloropsis salina produced more lipids (and higher quality lipids) when nitrate and phosphate levels were below 1ppm.

In many nations, large ponds of Nannochloropsis are used to strip nitrate and phosphate from agricultural effluent. In the Reef Aquarium, the same cleansing occurs. Nannochloropsis soaks up all the nutrients around it and converts them into microalgal proteins, pigments and Golden Fats. This nutrition is then delivered, in a perfect single-celled package, into the mouths of hungry corals, clams and other finicky filter feeders. This versatile algae can be fed directly to the reef or used to accelerate a culture of zooplankton such as rotifers, copepods or artemia. Green and gut-loaded live feeds open an awesome Pandora's Box! Algae allows the research aquaculturist, the commercial farmer and home hobbyist alike to engage with an ever-expanding array of species–allowing them to keep the unkeepable–breed the unbreedable–and bring the worlds of the Reef Aquarium and Aquaculture to ever-greater heights!

Abidin, A. A. Z., & YUSOF, C. Y. Z. N. B. (2021). Carotenogenesis in Nannochloropsis oculata under Oxidative and Salinity Stress. Sains Malaysiana, 50(2), 327-337.

Abdelghany, M. F., El-Sawy, H. B., Abd El-hameed, S. A., Khames, M. K., Abdel-Latif, H. M., & Naiel, M. A. (2020). Effects of dietary Nannochloropsis oculata on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, immune responses, and resistance against Aeromonas veronii challenge in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 107, 277-288.

Bongiorno, T., Foglio, L., Proietti, L., Vasconi, M., Moretti, V. M., Lopez, A., ... & Parati, K. (2022). Hydrolyzed microalgae from biorefinery as a potential functional ingredient in Siberian sturgeon (A. baerii Brandt) aquafeed. Algal Research, 62, 102592.

Chen, T. Y., Lin, H. Y., Lin, C. C., Lu, C. K., & Chen, Y. M. (2012). Picochlorum as an alternative to Nannochloropsis for grouper larval rearing. Aquaculture, 338, 82-88.

Chua, E. T., & Schenk, P. M. (2017). A biorefinery for Nannochloropsis: Induction, harvesting, and extraction of EPA-rich oil and high-value protein. Bioresource technology, 244, 1416-1424.

Comerford, B., Álvarez-Noriega, M., & Marshall, D. (2020). Differential resource use in filter-feeding marine invertebrates. Oecologia, 194(3), 505-513.

Converti, A., Casazza, A. A., Ortiz, E. Y., Perego, P., & Del Borghi, M. (2009). Effect of temperature and nitrogen concentration on the growth and lipid content of Nannochloropsis oculata and Chlorella vulgaris for biodiesel production. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 48(6), 1146-1151.

Ding, Y., Chen, N., Ke, J., Qi, Z., Chen, W., Sun, S., ... & Yang, W. (2021). Response of the rearing water bacterial community to the beneficial microalga Nannochloropsis oculata cocultured with Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture, 542, 736895.

Ding, D. S., Sun, W. T., & Pan, C. H. (2021). Feeding of a Scleractinian Coral, Goniopora columna, on Microalgae, Yeast, and Artificial Feed in Captivity. Animals, 11(11), 3009.

Faulk, C. K., & Holt, G. J. (2005). Advances in rearing cobia Rachycentron canadum larvae in recirculating aquaculture systems: live prey enrichment and greenwater culture. Aquaculture, 249(1-4), 231-243.

Galand, P. E., Remize, M., Meistertzheim, A. L., Pruski, A. M., Peru, E., Suhrhoff, T. J., ... & Lartaud, F. (2020). Diet shapes cold‐water corals bacterial communities. Environmental microbiology, 22(1), 354-368.

Gopakumar, G., & Santhosh, I. (2009). Use of copepods as live feed for larviculture of damselfishes. Asian Fisheries Science, 22(1), 1-6.

Hagiwara, A., Balompapueng, M. D., Munuswamy, N., & Hirayama, K. (1997). Mass production and preservation of the resting eggs of the euryhaline rotifer Brachionus plicatilis and B. rotundiformis. Aquaculture, 155(1-4), 223-23

Hirayama, K., Maruyama, I., & Maeda, T. (1989). Nutritional effect of freshwater Chlorella on growth of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. In Rotifer Symposium V (pp. 39-42). Springer, Dordrecht.

Hsu, C. H. (2000). Effects of food types and temperature on the development and reproduction of Apocyclops royi (copepoda, cyclopoida).

Kholif, A. E., Gouda, G. A., & Hamdon, H. A. (2020). Performance and milk composition of Nubian goats as affected by increasing level of Nannochloropsis oculata microalgae. Animals, 10(12), 2453.

Machinandiarena, L., Müller, M., & López, A. (2003). Early life stages of development of the red porgy Pagrus pagrus (Pisces, Sparidae) in captivity, Argentina. Investigaciones marinas, 31(1), 5-13.

Minturo, G. J., Noorain, R., Hitam, S. M. S., Shoiful, A., Azni, M. E., Ernawati, L., ... & Mohamad, R. (2022, April). Immobilized Nannochloropsis oculata in a down-flow hanging sponge (DHS) reactor for the treatment of palm oil mill effluent (POME). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1017, No. 1, p. 012024). IOP Publishing.

Nelson, S. G., & Wilkins, S. D. (1994). Growth and respiration of embryos and larvae of the rabbittish Siganus randalli (Pisces, Siganidae). Journal of fish biology, 44(3), 513-525.

Olivotto, I., Capriotti, F., Buttino, I., Avella, A. M., Vitiello, V., Maradonna, F., & Carnevali, O. (2008). The use of harpacticoid copepods as live prey for Amphiprion clarkii larviculture: effects on larval survival and growth. Aquaculture, 274(2-4), 347-

Ostrowski, A. C., & Divakaran, S. (1990). Survival and bioconversion of n− 3 fatty acids during early development of dolphin (Coryphaena hippurus) larvae fed oil-enriched rotifers. Aquaculture, 89(3-4), 273-285.

Pal, D., Khozin-Goldberg, I., Cohen, Z., & Boussiba, S. (2011). The effect of light, salinity, and nitrogen availability on lipid production by Nannochloropsis sp. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 90(4), 1429-1441.

Sharifah, E. N., & Eguchi, M. (2011). The phytoplankton Nannochloropsis oculata enhances the ability of Roseobacter clade bacteria to inhibit the growth of fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. PLoS One, 6(10), e26756.

Sirakov, I. N., & Velichkova, K. N. (2014). Bioremediation of wastewater originate from aquaculture and biomass production from microalgae species-Nannochloropsis oculata and Tetraselmis chuii. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 20(1), 66-72.

Su, C. H., Chien, L. J., Gomes, J., Lin, Y. S., Yu, Y. K., Liou, J. S., & Syu, R. J. (2011). Factors affecting lipid accumulation by Nannochloropsis oculata in a two-stage cultivation process. Journal of Applied Phycology, 23(5), 903-908.

Sumiarsa, G. S., & Imanto, P. T. (2009). EFFECT OF MICROALGAE ON GROWTH AND FATTY ACID PROFILES OF HARPACTICOID COPEPOD, Tisbe holothuriae. Indonesian Aquaculture Journal, 4(2), 139-146.

1 1 PAR= μmol photon m-2s-1 of photosynthetically active light