BFCM 30% OFF ALL LIVE FEEDS

Every live feed is 30% off—Tisbe, Apocyclops, Rotifers, Phyto, and more. Limited-time BFCM deal!

Rotifers may be minute in size, but they play an outsized role in coral reef aquariums. Often nicknamed “wheel animals” for the whirling crown of cilia on their heads, rotifers (especially the species Brachionus plicatilis) have become indispensable in the reef hobby. Reef aquarists and marine biology enthusiasts value these tiny plankton as nutrient-rich live food that can dramatically improve coral growth and health. In this comprehensive pillar guide, we’ll explore what rotifers are, their fascinating natural history and resilience, and why these tiny creatures are a powerhouse food source for corals and fish in reef tanks. By understanding how rotifers function in both nature and aquariums, you’ll discover how to harness this “little” secret to achieve healthier corals, robust fish larvae, and a more vibrant reef ecosystem.

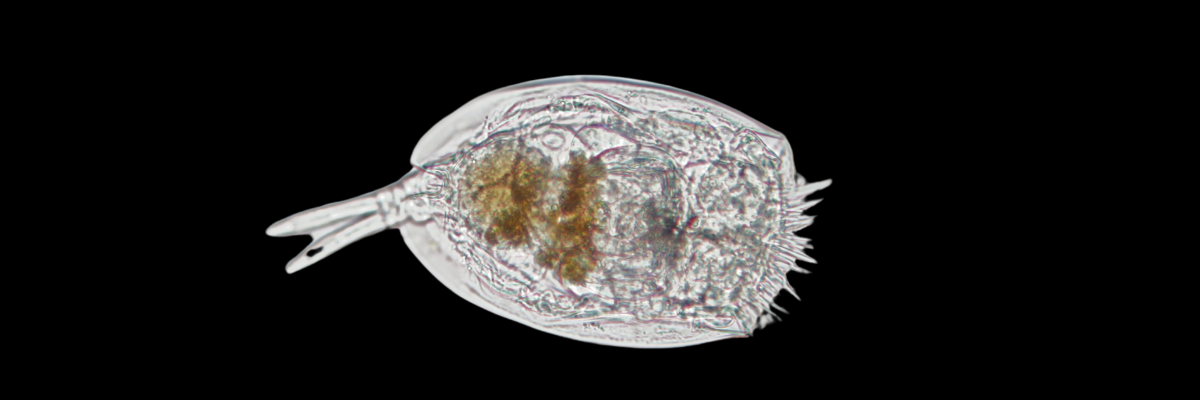

Main image: a microscope view of a single rotifer (Brachionus sp.) showing the wheel-like corona of cilia at its head. These beating cilia create water currents for feeding, inspiring the historic nickname "wheel animalcule." Despite their size, rotifers like this have a big impact in reef ecosystems.

Rotifers are microscopic multicelled invertebrate animals typically measuring only about 50 to 500 micrometers in length. They belong to their own phylum, Rotifera, and are found in freshwater and marine environments worldwide – from moss and puddles to lakes and oceans. The name “rotifer” comes from the Latin for “wheel bearer,” referring to the creature’s distinctive crown of cilia on its head called a corona, which rotates like a wheel when beating to create water currents for feeding. Early microscopists were enchanted by this appearance – rotifers were first described in 1696 by Rev. John Harris, and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek gave a detailed account of these “wheel animalcules” by 1703. Today roughly 2,000 species of rotifers have been identified (with likely many more undiscovered), showcasing a remarkable diversity of shapes and habitats.

Despite their minute size, rotifers are true animals with complex anatomy. Under a microscope one can observe a head, a trunk, and often a foot with tiny toes for grasping surfaces. The beating ciliary corona at the head not only propels the rotifer but also funnels in food. Just behind the corona is a set of hard jaws called trophi, which grind up food particles – typically microalgae and organic detritus. These key features (the ciliary “wheel” and the trophi jaws) are what define a rotifer. Internally, rotifers have a simple gut and other organs packed into a transparent, gelatinous body.

Some rotifers are free-swimming plankton, while others inch along surfaces like worms, and a few are sessile (living in tubes attached to substrates). A number of species can even form colonies of dozens to hundreds of individuals linked together, though most rotifers live solitary lives. This incredible variety in form and lifestyle is part of what makes rotifers so successful in many environments.

Rotifers have a fascinating natural history characterized by adaptability and resilience. They inhabit virtually any watery habitat – fresh waters, brackish estuaries, and even marine seas (though the vast majority of rotifer species are freshwater). In reef ecosystems, rotifers thrive in plankton-rich waters and on seafloor sediments, feeding on microalgae and bacteria and in turn becoming prey for larger animals. You won’t see them with the naked eye during a reef dive, but under the microscope rotifers from reef water are clearly identifiable. They play a key role in the food web by consuming tiny microbes and themselves being consumed by larval fish and coral polyps. This position as middlemen in the planktonic food chain makes rotifers ecologically important far beyond their size.

One remarkable survival trick is many rotifer species’ ability to withstand harsh conditions by entering dormancy. When environmental conditions deteriorate (food scarcity, drying, or extreme temperatures), rotifers can produce resting eggs or cysts. In many rotifer species, all individuals are female during good times, reproducing asexually via parthenogenesis (essentially cloning themselves by laying unfertilized eggs that hatch into more females). This allows populations to explode quickly when food is abundant. If things turn bad, however, rotifers switch strategy: they start producing male rotifers and undergo sexual reproduction, yielding special thick-walled fertilized eggs. These eggs enter a dormant state akin to anhydrobiosis (“life without water”). The rotifer essentially dries up into a tiny durable cyst that can survive desiccation or other stresses for long periods. Once favorable conditions return (water and food), the cysts can hatch and the rotifers spring back to life. This adaptation has let rotifers survive in ephemeral water bodies for millions of years. (Recent studies even managed to revive frozen rotifers that had been sealed in Siberian permafrost for 24,000 years, demonstrating their incredible endurance!)

Rotifers’ high tolerance for environmental fluctuations is also evident in species like Brachionus plicatilis, which can thrive across a wide range of salinities. While most rotifers stick to fresh water, B. plicatilis is euryhaline; it naturally lives in brackish salt ponds and can tolerate salinities from low brackish up to full-strength seawater (as long as changes are gradual). This flexibility partly explains why B. plicatilis has become one of the most important rotifers in marine aquaculture and the reef aquarium hobby.

Viewed up close, a rotifer might remind you of a tiny mechanical creature. The corona of beating cilia at the head appears as rotating wheels under magnification, pulling water and food toward the mouth. Through the transparent body, you can often see internal organs; rotifers have a simple nervous system and even a primitive eyespot in some species. Muscles allow them to contract and extend their bodies. Many have a tail-like foot with sticky toes, letting them temporarily attach to surfaces or inch along like a leech when not swimming. Others forego the foot and remain planktonic, freely drifting in the water column. Rotifers are generally filter feeders, using their ciliary corona to sweep up algae, bacteria, and detritus. (Some larger rotifer species are known to be raptorial or predatory, feeding on smaller protists or even other rotifers, but Brachionus and most common genera are herbivorous filter-feeders.) Their trophi “jaws” grind food efficiently, and waste is expelled through an anus near the tail end.

In terms of size, rotifers are among the smallest animals on Earth. Most species measure around 0.1–0.5 mm long (about the size of a grain of salt), though some can be as small as ~50 µm and a few giants reach 2–3 mm. Brachionus plicatilis, the rotifer most reef keepers encounter, is on the larger side of this range. An adult B. plicatilis is typically 150–360 µm in length – visible as a tiny speck under a magnifying glass. For comparison, another commonly cultured rotifer, Brachionus rotundiformis (the “S-type” rotifer), is a bit smaller (~100–200 µm). Both sizes are microscopic and ideal as live planktonic food, but aquarists often prefer the larger B. plicatilis (known as the L-type rotifer) because it’s a bit easier to handle and is still easily consumed by small larvae and corals.

Rotifers move slowly, either by rowing through the water with their cilia or by crawling on surfaces. In a tank, they tend to disperse evenly throughout the water column, which is excellent for feeding purposes. Their slow motility and small size mean even stationary or slow-moving predators (like coral polyps or delicate fish fry) can capture them without expending much energy. This makes rotifers exceptionally convenient as a first food for tiny reef creatures.

The life cycle of rotifers is another crucial aspect of their biology that contributes to their success. Under optimal conditions (ample food and stable water quality), rotifers reproduce extremely fast through parthenogenesis. A single female can produce a new daughter every day or faster, and those daughters themselves mature and reproduce within a day, leading to exponential population booms. This rapid asexual cloning allows rotifer cultures to double in a matter of hours. When overcrowding or poor water quality threatens the population, rotifers switch to sexual reproduction and resting egg production as a survival fallback.

For aquarists, this means rotifer populations can grow quickly but can also crash if conditions falter (e.g. if food runs out or ammonia builds up). In nature and in culture, rotifers thus exhibit boom-and-bust cycles, but their dormant cysts ensure the lineage carries on even after a crash. This resilience is one reason rotifers are considered so reliable as a live food source – even if a culture crashes, you can often restart it from hardy resting eggs.

When reef aquarists talk about using “rotifers” as food, they are almost always referring to Brachionus plicatilis, an L-strain rotifer that has become a staple live food organism in the marine aquarium world. B. plicatilis has a long history in aquaculture it was first utilized in the 1960s to raise marine fish fry in Japan and soon proved indispensable for rearing tiny larvae that refused to eat non-live foods. Since then, Brachionus rotifers have been a primary first food for countless marine fish and invertebrates in hatcheries around the globe. The reason? Their size and nutritional flexibility are perfect for newborn fish that require minuscule prey. Baby clownfish, for example, have tiny mouths and limited energy; a cloud of B. plicatilis rotifers in the water lets them constantly graze without having to chase food, dramatically improving survival in captivity. Rotifers have become famously associated with clownfish breeding. Clownfish larvae will greedily eat rotifers as one of the only foods they can swallow in the first days of life.

For reef aquarium keepers, B. plicatilis is valued not just for fish breeding but also as an ideal coral food. In the wild, many corals (especially small-polyp stony corals) capture tiny zooplankton at night. In a closed reef tank, providing live rotifers mimics this natural diet. B. plicatilis rotifers have a transparent, teardrop-shaped body and swim weakly, making them easy targets for coral polyps. Their size (~200 µm) is just right for even small coral mouths to ingest and digest. At Pod Your Reef (a company specializing in live plankton for reef tanks), B. plicatilis is described as “the most suitable for reef tanks” among rotifers. This species’ tolerance for full-strength saltwater and its relatively larger size means it delivers more nutrition per individual and survives long enough in the tank for corals to grab them. Rotifers can even reproduce in the aquarium if conditions permit, setting up a renewable plankton supply (though in practice, most rotifers will be eaten before reproducing, unless they’re in a refugium). Their prolific reproduction is still a benefit in culture.

In professional cultures, B. plicatilis is typically raised in marine saltwater (around specific gravity 1.023–1.025) at moderate temperatures (~24 °C / 75 °F). They are fed dense suspensions of microalgae like Nannochloropsis (a nutritious phytoplankton) to gut-load them with vitamins and fatty acids. As a result, the rotifers become little nutrient packets ready to be fed to reef tanks. When added to a reef aquarium, rotifers stay suspended in the water column and can stimulate a natural feeding response from fish and corals. Aquarists often “dose” live rotifers at night or before lights-out, when corals extend their tentacles to feed. Because B. plicatilis is so small and non-predatory, it poses no risk to even the tiniest reef inhabitants – it won’t attack larvae or harm coral polyps; its only role in the tank is as food and as part of the live plankton community. Some hobbyists report that after introducing live rotifers regularly, their corals display better polyp extension and coloration, likely due to the steady supply of natural prey. Even filter-feeding invertebrates (like certain sponges, feather duster worms, and small anemones) can consume rotifers, so the whole reef ecosystem benefits from their presence. Overall, B. plicatilis has earned its reputation as “the perfect SPS coral food,” boosting growth and vitality of corals when included in the feeding regimen.

Fun Fact: In addition to B. plicatilis (considered a larger “L-type” rotifer strain), there are also smaller strains (B. rotundiformis, or “S-type” rotifers) that some advanced reef breeders use for extremely small-mouthed larvae or coral spawn. However, S-types are a bit more finicky to culture and not as commonly sold for hobby use. Most reef keepers will do just fine sticking with the hardy B. plicatilis, the L-type rotifer.

One might wonder: what makes rotifers so nutritious? These tiny creatures are often described as “little bags of nutrients” or “living soup” for your reef. In terms of basic composition, rotifers can be extremely protein-rich – studies and culture guides indicate rotifers are roughly 50–65% protein by dry weight. This is an exceptionally high protein content, comparable to or even exceeding that of Artemia (brine shrimp) and many other live feeds. Protein is critical for growing fish larvae and for corals that need amino acids to build their tissues, so rotifers provide a potent dose. Rotifers also contain lipids (fats) and some carbohydrates; however, their fatty acid profile is what really shines when they are cultured on the right diet. If rotifers are fed marine phytoplankton (especially algae like Nannochloropsis or Isochrysis), they become loaded with highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs). HUFAs such as DHA and EPA are essential omega-3 fatty acids that young marine animals require for healthy development of nervous systems, cell membranes, and overall growth. Many marine fish larvae cannot synthesize enough of these fatty acids on their own and rely on diet to obtain them. Rotifers enriched with HUFA-rich algae thus become an ideal delivery vehicle for these crucial nutrients. It’s reported that rotifers can even carry vitamins and minerals present in their feed; for instance, vitamin profiles of rotifers will mirror the algae or yeast they eat. This makes them a customizable food – aquarists can fortify rotifers with specific nutrients (a process known as gut-loading or enrichment) before feeding them to reef animals.

It is important to note that a rotifer’s nutritional value comes largely from its gut contents and biochemical makeup, which in turn depend on what the rotifer itself has been eating. As one aquaculture guide bluntly puts it: “rotifers have no nutritional value themselves; it is the algae they consume that provides this.” In other words, a rotifer is a vector for nutrients – if you feed the rotifer poor-quality food (e.g. plain yeast or rice flour), the rotifer will be nutritionally poor. But if you feed it DHA-rich microalgae, the rotifer becomes a DHA-rich morsel. For this reason, the best rotifers for reef tanks are those cultured on marine microalgae diets. Nannochloropsis oculata, for example, is often cited as an optimal feed for rotifers because it’s high in HUFAs and has a cell wall that resists quick decomposition. Rotifers raised on such algae have superior HUFA content and greatly benefit the health of fish larvae and corals that eat them. By contrast, rotifers grown on baker’s yeast (sometimes used for convenience) might keep the rotifer population going, but their HUFA levels plummet – they become basically “empty calories” with protein but lacking essential fatty acids. Hobbyists purchasing live rotifers from reputable sources can usually trust that those rotifers have been fed on nutritious phytoplankton.

From a coral’s perspective, a rotifer is like a little package of protein and fat that’s just the right size to digest. Scientific analyses show rotifers can be about 60% protein and 10–20% fat (exact values vary with diet and strain), plus some carbohydrates and various micronutrients. This composition is comparable to many of the zooplankton that corals consume in the wild. Additionally, because rotifers are soft-bodied (with no hard exoskeleton), corals can digest them relatively easily. There’s little waste; nearly the entire rotifer can be broken down and absorbed by a hungry coral polyp, unlike, say, a copepod that has a tougher exoskeleton. This easy digestibility, combined with their high protein and HUFA content, is why rotifers are considered high-quality coral food. Corals that feed on rotifers regularly can show improved growth rates and better tissue expansion, since they’re consistently getting crucial building blocks (amino acids, fatty acids) from the zooplankton side of their diet. Even photosynthetic corals (which get some energy from light via their symbiotic zooxanthellae algae) benefit from supplemental rotifer feedings; the extra nutrition can be used for reproduction, tissue repair, and laying down skeletal growth. In short, rotifers offer a nutrient-dense snack for any reef organism that can catch them. As one reef aquarist guide summarizes: “We can think of them as mighty mini lunch bags loaded full of nutrients” for our corals.

For reef hobbyists, adding rotifers to a tank can yield numerous benefits for corals, fish, and the overall ecosystem. Below are some of the key reasons rotifers are treasured as a live food in reef aquaria:

Perfect Size for Coral Feeding: Small-polyped stony corals (SPS corals like Acropora or Montipora) have tiny mouths often under 1 mm in diameter. Rotifers, being only ~0.1–0.3 mm, are easily captured and ingested by even the smallest coral polyps. Unlike larger foods, rotifers do not overstress coral mouths or get rejected. Their minute size also means corals can capture many prey items per feeding session, maximizing energy intake.

Easy to Digest: Rotifers have a soft body with no chitinous shell, so corals can digest them fully. This yields more nutritional gain per prey captured. Hobbyists report that corals readily accept rotifers and often show an enthusiastic feeding response (extended tentacles, rapid ingestion) when rotifers are present, indicating how suitable they are as coral cuisine. Corals seem to recognize rotifers as natural prey.

High Nutrient Content: As discussed above, rotifers are packed with protein and essential fatty acids when raised on a good diet. Each rotifer is like a “miniature nutrient bomb.” One article aptly calls them “mighty mini lunch bags loaded full of nutrients,” which leads to healthier, more vibrant corals. Regular feedings of rotifers can enhance coral coloration and growth. Even fish and other invertebrates benefit from eating rotifers; for example, finicky planktivorous fish will snap them up, and filter-feeders like feather duster worms or small clams can consume rotifer-sized particles. The whole reef community can gain extra nutrition from a rotifer infusion.

Natural Behavior and Activity: Introducing live rotifers triggers natural predatory behavior in your tank. Corals will extend their polyps to catch the moving prey, and fish will actively hunt the swarming rotifers in the water column. This can be enriching for the animals, much like how zoo animals are given live food to stimulate their hunting instincts. Fish that might ignore stationary foods often can’t resist the allure of live rotifers. The presence of live plankton also enhances your tank’s microfauna diversity, contributing to a more dynamic and balanced ecosystem. Any rotifers that escape immediate predation may even reproduce in the tank and help consume excess microalgae or detritus, acting as part of the cleanup crew on a microscopic level.

Rapid Reproduction and Colonization: Rotifers multiply so quickly that a small starter population can yield millions of individuals in a short time. In practical terms, this means they are readily available and affordable as live feed. You can continuously culture them (though we won’t delve into culturing methods here) or buy them in large quantities without breaking the bank. Their fast reproduction also means even new reef hobbyists can keep a culture going successfully, ensuring a steady supply of fresh food. In a reef tank, a full rotifer “colony” is unlikely to establish long-term (due to constant predation and filtration), but dosing rotifers regularly can maintain their presence. And unlike larger “pod” species, rotifers pose no risk of overpopulation plagues – if by chance too many rotifers are present, they’ll become coral and filter-feeder snacks or die off without fouling the tank. (Any surplus rotifers are generally filtered out or eaten quickly in a healthy reef system.)

Enhanced Coral Resilience: There is emerging evidence that feeding corals with nutritious zooplankton like rotifers can improve their stress tolerance. For instance, a study on Acropora corals found that under stressful high-CO₂ conditions (simulating future ocean climate change), corals that had access to rotifers (B. plicatilis) ramped up their feeding and were able to increase their tissue lipid stores compared to unfed corals. The extra fat reserves act as an energy buffer, potentially helping corals cope with thermal stress or bleaching events. In that scenario, rotifers literally fattened up the corals, improving health indicators. In general, well-fed corals can better withstand stress than undernourished ones, so providing rotifers as supplemental food is a strategy many aquarists use to help corals thrive, especially in high-growth setups or SPS-dominated tanks where nutrient demands are high.

Cleaner Feeding Option: Compared to some other coral foods, rotifers (especially live rotifers) do not quickly degrade water quality. They remain alive in the tank until eaten, so they won’t pollute the aquarium by decaying uneaten (unlike, for example, overfeeding a frozen food, which can rot if not consumed). This makes rotifers a relatively “clean” feed. You can target-feed rotifers to corals with a turkey baster or dosing pump without worrying that any leftovers will foul the tank. Whatever isn’t eaten will likely be removed by filtration or remain alive for a while, giving tank inhabitants multiple chances to snack on them.

To sum up, adding rotifers to your reef tank establishes a richer food web that mirrors the ocean. As one reef care article put it, “adding rotifers to your tank establishes a good base and variety of food sources for your system, which is always a huge advantage to keeping a healthy reef.” Corals, fish, and invertebrates all find nutritional value in these tiny critters, and their presence can boost the overall vitality of the ecosystem. It’s no wonder that many successful reef keepers consider live rotifers a secret weapon for coloring up corals and conditioning fish for spawning.

Rotifers’ benefits don’t stop at being food. Scientists are now exploring innovative uses for rotifers in coral conservation and health, leveraging their ability to carry content in their gut. A groundbreaking study in 2020 demonstrated that Brachionus plicatilis can act as a vector to deliver probiotic bacteria to corals. In this research, rotifers were fed a cocktail of beneficial microbes (BMCs – Beneficial Microorganisms for Corals) intended to boost coral resistance to stress. The rotifers readily ingested the probiotic bacteria, which filled their digestive tract and even coated their surface, essentially turning each rotifer into a living pill full of medicine. When these enriched rotifers were introduced to coral colonies (Pocillopora damicornis), the coral polyps eagerly captured and ate the rotifers, thereby delivering the probiotics into the coral’s gastric cavity. This method effectively shuttles helpful bacteria into the coral in a targeted way. The rotifer itself provides nutritional value to the coral, and simultaneously the coral gets a dose of probiotics that can aid its microbiome. Researchers noted that corals readily ingest rotifers (as any reef aquarist would expect) and highlighted this approach as a promising technique for administering probiotics to corals in situ on wild reefs. It’s a clever symbiosis: rotifers, already a natural coral food, can be “loaded” with extra beneficial content to help coral health.

This probiotic delivery concept is part of a larger effort to help corals withstand climate change (often called “probiotic therapy” for corals). The fact that B. plicatilis increased coral lipid levels under high CO₂ stress in another experiment further underscores that rotifers may improve coral resilience both directly (via nutrition) and indirectly (via microbiome enhancements). For reef aquarists, such scientific developments hint at future products where rotifers might come pre-loaded with symbiotic algae or bacteria to improve coral health. Even now, some hobbyists dose live phytoplankton along with rotifers, effectively creating a micro gut-loaded feed that could support coral and filter-feeder microbiomes. While these advanced uses are still being studied, it is fascinating to realize that rotifers – among the simplest of animals – could play a high-tech role in reef restoration and advanced aquarium husbandry. The takeaway is that rotifers are incredibly versatile: they are not only a nutritious snack but also a potential carrier for other beneficial substances in reef ecosystems.

From their first discovery as curious “wheel animalcules” in the 17th century to their modern prominence in reef aquariums, rotifers have proven to be tiny yet mighty. In terms of natural history, they are marvels of miniaturization – complex multicellular animals that can survive extreme conditions and reproduce at astounding rates. For reef hobbyists, rotifers like Brachionus plicatilis represent a bridge between the microscopic world and our corals and fish. They encapsulate what makes reef ecosystems thrive: the transfer of energy and nutrients from the smallest of plankton to the larger, more visible creatures we love to keep. By incorporating rotifers into our feeding routines, we essentially invite an important piece of the wild ocean’s food web into our tanks. The result can be healthier, more colorful corals, robust fish fry, and an overall more dynamic aquarium ecosystem.

In education and practice, rotifers teach us that even the humblest organisms can have outsized impacts. Their rich nutritional profile fuels the early growth of fish and corals alike, and their presence stimulates natural behaviors in our tanks. As research pushes boundaries, rotifers may also help deliver solutions for coral disease and climate resilience, showing that innovation in reef care can come in very small packages. In short, the history of rotifers – from pond-water curiosities to essential reef aquarium food is a story of big benefits coming from microscopic life. Reef hobbyists who embrace these little “wheel bearers” will find that they truly can help turn the wheels of a thriving reef ecosystem, one tiny rotifer at a time.